Chapter One: News Is a Manufactured Product

Welcome to the Bakery

News reporters are bakers. Ever heard this before? I don't think so, because I haven't, and I've probably read more journalism stuff than you have. Reporters may  be called watchdogs of democracy, guardians of free society, scandal-sniffing fiends lurking behind lapel mikes, muckrakers of, well, muck, weasels, rats, snakes, jackals, or just plain ol' running dogs. But they are seldom called bakers.

be called watchdogs of democracy, guardians of free society, scandal-sniffing fiends lurking behind lapel mikes, muckrakers of, well, muck, weasels, rats, snakes, jackals, or just plain ol' running dogs. But they are seldom called bakers.

Yet as skilled professionals, journalists and bakers have a lot in common. Using common raw ingredients and a formula, they manufacture a product consumed daily by nearly everybody. The best bakeries make new bread all day long, because bread gets stale quickly, just as news gets old quickly. We don't usually buy day-old bread, so the baker needs to sell that bread promptly to stay in business. As for news, sometimes we don't even want it an hour old.

News, then, is both a perishable product and a manufactured one, sold to earn money for its purveyor. We call that process "making news."

If you buy that concept, you've already come a long way toward understanding news in general, and local news in particular.

Most Americans can see that news has to be timely and that its producers are in business for profit, but consumers have a harder time seeing the manufacturing side of news. Let's take an example from real life. Suppose you got up this morning around 7:30. You took your usual shower, got dressed, poured some puffed rice cereal into a bowl, and mixed up a mug of instant coffee or maybe grabbed a diet cola. You switched on the TV, fed the hamster, greeted family members or roommates, maybe checked out Facebook, and then set out for work or school.

Is what you did news? Nope.

But it could be. I can make a news story out of that morning routine of yours. Watch:

The water department was busy today, providing Irving Fern of Nernville with water for a shower, a flush, and a cup of coffee. His routine began at 7:30 a.m. with a breakfast of puffed rice cereal and milk, before he left for the office.

Don't think much of that news story? Okay, how about this one:

A bowl of cornflakes and coffee. That's how millions of Americans start their day. Irving Fern of Nernville, however, puts a different twist on it: he lays in a stash of puffed rice for those early morning routines.

Or maybe this:

Television is an early morning ritual for many Americans, and Irving Fern of Nernville is no exception. Each day he begins with a ritual of cereal, coffee, and The Morning Show on KRUD-TV.

In fact, any one of billions of events every day could potentially become news, and could be presented to the world by news media. News is made by selecting certain events and manufacturing a product that is then displayed for consumers until it becomes old, is discarded, and replaced by another.

News is a manufactured product. It is not an event. It is not an interview. It is not a meeting. It is not a terrorist attack. It may be based on those things, but it is a manufactured product separate from them.

Manufactured products like bread can contain on all kinds of ingredients. But usually the manufacturer chooses the same ones again and again, because they have traditionally added up to the best product, the one most likely to sell at a profit. News is manufactured the same way, and its ingredients have evolved over a couple centuries of trial and error on our way to modern media principles of Western media. Journalists can't just write whatever comes into their heads—although it might appear that way sometimes. They relay on principles, and they learn them in communication schools, on the job, or instinctively through a lifetime of exposure—and through their ability to reflect what our society values.

What We Value

1. We Want It Now.

Don't you like to be first to pass on at item of gossip? Don't you hate stale bread? News is the plural of new. There's an old saying among news editors: So you got a Pulitzer Prize yesterday. What have you done for me today? Reporters hang their respect and credibility on being the first to report something, while editors and news directors hang promotions and pay raises on those who bring back the scoops. Journalists assume that consumers don't care about the publication that comes in second, and usually they are right. We value first place: no one remembers silver medal winners. No one recalls vice presidents. No one memorizes past Oscar nominees. Reporters pride themselves on being fast and being accurate, but if they have to be one or the other—well, you can always make corrections later.

That's why it's risky to put much faith in a quickly breaking story. Some of us may remember the death of Princess Diana. First she was reported to have been in a car accident. Then she was injured. Then, "update" (correction), she was dead. The Gulf War of 1991? All those smart bombs landed accurately on a dime. Well, not really, we find out later. The World Trade Center attack? Some 50,000 people worked in those buildings, television reporters told us initially, or walked the streets underneath. A few hours later we learn the figure was actually 5,000, bad enough. Well, maybe about 3,000, the more accurate figure developing as reporters obtained better information.

The value of timeliness is certainly among the oldest journalistic values, but it still requires better reason than simply the drive to keep a hungry audience right up to date. Consumers do not highly value news people who repeatedly arrive late at the gate; viewer ratings for broadcast outlets that get scoops (and, of course, repeatedly remind viewers of that) are traditionally higher.

Newspapers try to compete by working smarter: by buttonholing a politician after the press conference to obtain that special comment; by making news out of ongoing stories—say, an investigation on gangs and drugs in the city; often by making old things appear new.

Let's say your city hall burned to the ground last night. Of course, a good radio news team picked that up immediately—all they had to do was run over with a telephone close and talk to listeners. The newspaper reporter and photographer were also on hand immediately. Television is habitually a bit slower, bogged down by video equipment and technicians, because television news can't function without a camera or digital video. After all, would you watch a television broadcast of a fire without any pictures? But TV news teams can work fast when they have to, almost to radio standards, so they'll have the story at morning newstime.

What about that newspaper reporter and photographer? They might be able to put something together fast, even get it on the web, but their paying customers won't see it until the next morning in any case, (except for a few web regulars). So they resort to manufacturing a story a bit differently from their broadcast buddies.

Watching the television news, you might hear, "A fire tonight destroyed the Bigville city hall." In next day's paper, however, you might read, "Fire fighters still have not determined the cause of a fire that destroyed Bigville city hall last night."

Did anything change between the evening news and the morning daily? Not likely. But journalists at the paper adjusted their approach to sound new, honoring the news value of timeliness.

Timeliness is also part of the reason why you see larger market local TV news concentrate on murder and crime. It's common to see two minutes of an evening newscast (an enormous amount of time for local television news) devoted to a double-drug-dealing do-in on Dreary Drive behind the bus depot. The next day you pick up the paper and find the story—four grafs on page B14, toward the bottom. It's old news after everyone has seen it on TV, and what new can you say about another murder? Of course, if your photographer was on the scene, that's something else again.

2. We Want It Here.

What do you care if East Podunk's property taxes are going up 10 percent? Exactly, say news manufacturers. Let Podunk's media cover Podunk, and we'll cover our town. The principle that journalists ought to be intensely local in their focus has not changed despite by the end of the century 80 percent of newspapers, 70 percent of television news operations, and 72 percent of radio stations had absentee chain owners.

The farther away the story occurs, the less likely the manufacturing process is to take place, unless the journalist can find a "local angle." A classic "bus plunge" story ("Bus plunges over cliff, many die."), sadly familiar in some developing nations, will see little light in your town unless one of the victims was from the area. In fact, editors work all day long looking for local angles in wire stories. The story coming in on the wire from Washington announcing new agriculture grant winners may get legs if a news director can begin, "Frank Nern of Ourville is among five researchers awarded a $50,000 grant."

You may think this parochial logic applies only to local and regional journalists, but it doesn't. USA Today covers mostly today in the USA, though it sells world wide (aimed mostly at expatriates and traveling Americans). Network news emphasizes American material. The beat of these news operations may be large, but it's still inward-focused. Critics say this news value encourages provincialism and ignorance of the world. But it sells. The Christian Science Monitor, written and edited by some of the nation's best journalists in an attempt to fairly cover all the world, and not just our own puddle, has struggled financially for years.

3. So What?

When television news began in earnest in the early 1950s, viewers and producers alike wondered if it was really necessary. After all, newspapers provided everything the average American needed to know about the world, squeezed into a few dense pages of eight-point type with a few black-and-white photos. Why buy an expensive television ($400 in 1950!) when you could rely on a cheap (10 cents) newspaper?

This changed quickly, when Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy and his un-American hunters went out loaded for Communist bear. TV news covered the hearings, and broadcast journalist Edward R. Murrow (and others) disclosed the abuses. People realized they had to have a television for news—it clearly had consequence to their lives. Sales soared.

The Consequence Pyramid.

The trend toward emphasizing news of consequence to local reader,—"news you can use"—as feature editors often call it, can be cemented into a local news gatherer's "consequence pyramid." In gauging the consequences of an event and their potential to be manufactured into news, a reporter or editor will climb the consequence pyramid: The top of the pyramid the most important consequence involves your money.

This is America. Greatest capitalist nation the world has ever seen. If money doesn't come first here, what does? Philanthropy? That's money. Government help for the poor? That's money, too. The local politicians? They exist to spend your money. The hopes and dreams of advertisers? Advertisers would like news people to feature their hopes and dreams daily as leading news stories, but professional journalists have some integrity, usually. Still they will feature stories about money.

Below money on the consequence pyramid, we find items likely to affect your freedom of movement and decision. Americans live in a country built on the value of individual initiative and freedom from government interference. Any proposal that aims to curb such freedom is mighty interesting to a lot of folks, who will oppose it because it's not "the American Way." News people know this, and so are quick to point out how a proposed rule or regulation may affect you, personally.

If a prospective story raises neither money nor freedom issues, it may still affect your life by bringing death and destruction. (This is assuming it doesn't actually bring them to you, in which case you wouldn't be watching TV news.) But if the corner strip joint burns down, it's going to have consequences for someone (and maybe for more people than you think!). If the owner of the local supermarket dies, it may affect your shopping habits—but then we'd be back to the top of the pyramid again.

Fight! Fight! Fight! We like to watch a fight. We even like to get into fights, though you'd think a couple of world wars would have taught us a good lesson. But if we can't do either of those things right now, we like to read about fights, anyway. Newspeople know this, which is why a dreary city council meeting hits the front page above the fold when two commissioners clash over—oh, street maintenance?

As an example of the power of conflict to make a story, let's say you're a news reporter presented with today's city council agenda, which reads as follows:

1. Approval of minutes.

2. Approval of building permits.

3. Liquor license approval.

4. Third reading: abortion picketing ordinance.

5. Fifth Street road work update: city engineer.

6. Adjourn.

You need to make a quick guess at which item you'll most likely take out your microphone for. Which do you think most reporters will choose? Conflict drives ratings, and ratings drive job security, especially in the broadcast business where a bad sweep can mean a pink slip.

Reporters argue they must report controversy as a matter of fairness: to present an issue as if everyone agreed on it when they did not is to unjustly ignore all sides. Worse, it ignores information a reader needs to know to make up his or her mind on an important issue. True enough, but that doesn't explain why fights place so prominently in the news hole. Fisticuffs attract attention, at a bar or at a podium.

4. It's Who You Know.

You go out jogging and it starts to rain, so you go back home. Think a dozen news people follow you to write this into a news story? If you're the president of the United States, they do.

And they did—a few years ago just this story about George H. W. Bush was broadcast over national network news. Reporters know stories about famous people attract an audience, even if the gist of the story is utterly trivial. In fact, that seems to be more and more true as traditional news outlets add celebrity features to their pages and to their newscasts. The system feeds on itself: the more a celebrity is featured in the news, the more that person becomes a celebrity worth covering, until the original reason (which may have been minor) for the celebrity's status is almost forgotten. Why is she famous? Because she's a celebrity. Why is she a celebrity? Because she's famous—famous because her name and picture have become familiar.

You could argue that a feature on the president of the United States getting wet while jogging has more than just celebrity value—after all, he is the country's major elected leader and public servant. But how about the future housing plans of someone like O.J. Simpson, the notorious former football star? How about the obsequies of someone like Lady Di, the on-again-off-again, British royal? How about the frustrations of someone like Lindsey Lohan, the post-adolescent du jour? Why do we news consumers crave celebrity stories? Even newspeople themselves wonder. Most news purveyors who consider themselves ethical and respectable would rather not chase after the newest starlet, rich playboy, or vacationing royal. But power rules, and media power is based on circulation.

6. We Like Surprises.

Another old journalists' axiom: When dog bites man, it's not news. When man bites dog, that's news. Usually the perennial criticism that newspeople publish or broadcast "only bad news" has its basis in this news value. We know that 1.7 million people walk up an airline jetway every day and nearly always they walk down again safely. We could write a story about this: "Airline passengers in a hundred U.S. cities yesterday flew safely by plane to a number of destinations." If you read a story like that, though, what would you think? Probably the words "So what?" come to mind. It's normal. Normal is good for you and me—but not for newspeople.

If you had to read that story in 1920, however, it would be different. Then it would have been quite unexpected, and the unexpected makes news.

Usually things go along pretty well in this society, so the unexpected is a break from the norm—often a bad break, or "bad news." Accidents, muggings, bribes, disasters, terrorism, arrests, bankruptcies, closures, layoffs, lies, murders, lost cats, and mean dogs, standard fare for the local news, because they are unexpected. You might say that you expect muggings, you know accidents happen, and companies are always downsizing—so what's unexpected? But the reason you expect these things is not that they happen very often: it's because you've read about it so very often that you've grown more cynical about life. In your view of the world based on the media, the unexpected has become expected.

In real life, however, it's still unexpected. How many of us leave the house truly expecting to be mugged, arrested, laid off, or—heaven forbid—murdered? We may speak cynically about expecting the worst, but the reality is such these things don't happen very often. They really are surprises and, therefore, news. It is unfortunate that this news value has led people to view the world as the media portrays it, a view is dramatically skewed toward the negative. For instance, a recent poll showed that people believe crimes and accidents to be much more prevalent than they actually are, because their world view is based not on their own experience but on media reportage.

Reporters sometimes argue that they report the unexpected—particularly accidents—to fulfill their responsibility as society's guide to good behavior. The idea is that if you see a horrible photo of a mangled car after an accident, you'll be reminded to drive more safely—thus, the shocking photograph has redeeming merit. In fact, the history of automobile safety in America has proven this argument to be wishful rationalization offered by journalists who know a grisly scene above the fold sells newspapers. Automobile travel has gotten safer in the last thirty years, but that can't be attributed the news media. It is the result of government crackdowns on dangerously constructed cars and of new laws requiring seat belts, child seats and air bags, and imposing big penalties for drunk driving.

You may notice that nowadays fewer newspeople cover common (yet still unexpected) car accidents in any detail, and photos of wreckage have disappeared from most local newscasts and front pages. Maybe editors have decided to spare morning news consumers from breakfast-ruining car wrecks, or maybe these scenes have become "old fashioned" and no longer attract audience. Like clothing and furniture, media habits too go in and out of style.

And sometimes the expected can make news, too. If dog bites man, it's not news, says the sage, but if dog bites man while a video camera is rolling—details at 11.

7. We're All In This Together.

This section might also be headed "miscellaneous," because it's a catch-all for a huge variety of stories vaguely connected to what we'll call "news," but still deemed worth the manufacturing process. Generally, human interest pieces have one thing in common: emotional appeal. Newspeople know a story that touches hearts is likely to be read or listened to. Human interest, sometimes called "soft news" or "feature," is designed to make you happy, sad, compassionate, angry, even horny—in fact, to elicit just about any emotion except boredom, which is illegal in the media business. So you have the perennial heart-tug of little Debbie, a child cancer victim, holding up courageously under a grim series of chemotherapy. Will she romp and play again? Will she grow up to love and enjoy life? Will you contribute to her recovery fund? Don't you feel a tear just reading these words?

Such tragedies recur in all our towns, yet they never fail to interest viewers and readers, especially if the photography is "powerful"—that is, lets us into private and intimate moments of a family's tragic struggle. The media have many arguments for covering these tragic stories over and over: The family needs public contributions to pay its huge medical bills, or society needs to know the difficulties with which some of us must grapple so that we will be moved to do something. This argument has not led to social change, however; no little Debbies have persuaded Congress to enact national health insurance, and improvements in care have come from other sources than pitiful news stories. The influential Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) may know their P.R. But the group originated not from yet another sad story of drunk teenagers killed on their way to the prom, but from a particular mom who lost her own child in a drunk driving accident. Research on cancer has probably not been undertaken by physicians who read sad news stories, but on clinicians who relied on hefty grants and the Hippocratic oath.

Sad stories do, however, remind us of how lucky we are (a dose of shame to bring to your next therapy session), and may move some money the victim's way. In fact, in the case of the Grand Forks, North Dakota, flood of 1997, sad stories moved fifty million in McMoney from McDonald's founder Ray Kroc's widow to the famed "Angel Fund." That, however, is rare, and the story of 40,000 dispossessed by flood moves beyond merely "human interest." The big value of tear-jerk news stories is that they sell.

While newspeople know the two primal emotions of sex and fear will sell over and over and over, human interest stories in this area have generally slid into the non-news sensationalist media. Newspeople who consider themselves ethical professionals generally distance themselves from the tabloids or "tabloid TV," even  though a fair chunk of media consumers confuse these sensationalist efforts with reputable journalism. The confusion is, however, understandable. Modern news media were, after all, built on sensationalism: one of Benjamin Day's first big stories in his pivotally important penny-press newspaper, The New York Sun (1833), covered in agate-typed detail the story of a rich man, a prostitute, and a murder. Historians say this newspaper set the benchmark for modern journalism; perhaps modern news gatherers shouldn't be too disdainful of the earthier panderers around them.

though a fair chunk of media consumers confuse these sensationalist efforts with reputable journalism. The confusion is, however, understandable. Modern news media were, after all, built on sensationalism: one of Benjamin Day's first big stories in his pivotally important penny-press newspaper, The New York Sun (1833), covered in agate-typed detail the story of a rich man, a prostitute, and a murder. Historians say this newspaper set the benchmark for modern journalism; perhaps modern news gatherers shouldn't be too disdainful of the earthier panderers around them.

These Things We Value

These are time-honed news values of American journalism, and they help us to judge whether a particular event will undergo the manufacturing process. Of course, it's not as simple as that. News values are not considered separately but are assessed as a whole. For instance, an event that strongly figures into one news value, but contains none of the others, still may be ignored. If, for instance, I tie my shoes this morning, that's timely enough. ("Ross Collins today tied his shoestrings into a neat bow. The effort took him thirty seconds"), but it contains no other news values. If, on the other hand, I try to tie movie star Mel Gibson's shoelaces (does he have any?) and he punches me for doing it ("If it bleeds, it leads"—TV news axiom), we've got prominence and conflict. If I did it in the local arena and Gibson then stormed out in a huff, canceling his show, we have proximity and consequence of an unexpected event. If Gibson's poor treatment of a lowly teacher makes you angry (or better yet, moves you to pity), we have human interest. Page One stuff. Lead story of the newscast.

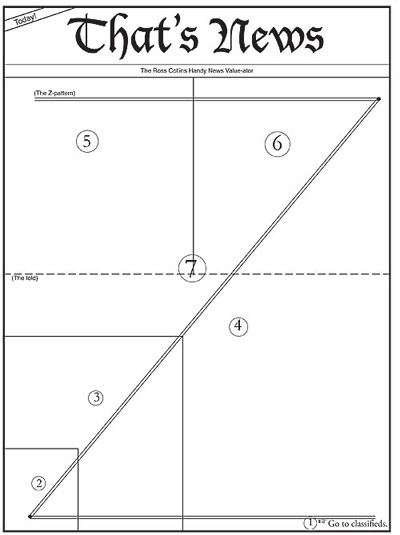

Lesser events, of course, warrant lesser treatment. How much? It depends, first, on the media outlet's view of reality, (see chapter 2) and, of course, on the whims of the gatekeepers. But as a lay person, you can predict the news value of any given event by using my News Value-ator.

Guide to the News Value-ator

* Timeliness

* Proximity

* Consequence

* Conflict

* Prominence

* Unexpectedness

* Human interest

Each of the news values above is worth one point, a half point if it's weakly present, and two points if it's strongly present. To predict a potential story's likely importance, determine the strength it reflects in each of the news values. A value of one point will likely not merit publication unless it's a slow news day. Add the points to determine its probable importance in a daily news-oriented publication, website, or news broadcast.

Each of the news values above is worth one point, a half point if it's weakly present, and two points if it's strongly present. To predict a potential story's likely importance, determine the strength it reflects in each of the news values. A value of one point will likely not merit publication unless it's a slow news day. Add the points to determine its probable importance in a daily news-oriented publication, website, or news broadcast.

In TV news, the more news values, the earlier the story appears in a broadcast and the more time it eats. Note that most local news broadcasts, not counting sports and weather, fill about 12 minutes' air time. This means that even stories offering a high News Value-ator score (above 4) may not appear. And a story that bloats to three minutes of news time must be important indeed—either because it holds a high news value score, or because it offers a combo of The Big Three, sure to draw readers during sweeps month.

As a newspaper story becomes more news value-able, it jumps to the top half of the page to reflect the Z-pattern: we generally scan a page from upper left to lower right. A news value of six or seven probably requires more coverage, including a main story, photos, graphs or charts, and a couple of sidebars.

Let's try an example from a typical newspaper. This was published, so presumably its news value-ation made the cut.

Download News Value-ator as pdf.

Headline: Governor calls for tax rebate

Lead: The governor of Minnesota yesterday asked state legislators to return almost $2 billion to taxpayers in the form of sales tax rebates. Democratic leaders, however, called the request "irresponsible," and noted that a looming recession could dry up surpluses in one biennium.

Let's analyze this story.

1. Timeliness: It happened yesterday, timely enough for the nature of the story. +1 point.

2. Proximity: Wouldn't play in Peoria, but for a Minnesota audience, +1 point.

3. Consequence: Again, for local readers, it hits that wallet. +1 point.

4. Conflict: Dems don't dig it. +1 point.

5. Prominence: The governor may be somewhat prominent, but not really the focus of this issue. +1/2 point.

6. Unexpected: May or may not be, though tax rebates certainly aren't the norm. +1/2 point.

7. Human interest: No real emotional tug in this political story. +0 points.

Total: 5 points.

Looking at your chart, you see this story would place fairly prominently on the upper left of the Z pattern as one of the day's major stories. And that's about where it appeared in Minnesota newspapers.

The News Value-ator is even more helpful when you want to predict the possibility that journalists will cover an event. We noted that any event could theoretically be made into news. What about our example from earlier in this chapter? We talked about a typical morning routine, and several possible ways that routine could be made into a news story. But would it be? The News Value-ator can help us find out.

1. Timeliness? Since it happens every morning, it is timely, although not in the sense of a single "event." Normally newspeople don't think of routine occurrences as "new." +0.

2. Proximity: Somewhat, for a local newspaper. +1/2.

3. Consequence: Hardly. +0.

4. Conflict: Ho-hum. +0.

5. Prominence: Am I Bill Gates? +0.

6. Unexpected: Only if the cereal didn't crackle. +0.

7. Human interest: Yawn. +0.

Total: 1/2 point. Skip to the comics.

But you already knew that little story couldn't become news, didn't you? Okay, let's try something less obvious. Your group is planning to meet next week and elect officers. Would that make news? Let's see.

1. Timeliness? Only if you let a news organization know immediately. If it happened two weeks ago, forget it. Either +1 or +0.

2. Proximity? Probably yes for your own ville, no for New York. (Even if you live in New York. It's a big place.) +1 or +0.

3. Consequence? Depends. Is your group the local chess league, or the City Commission? +1 or +0.

4. Conflict? Did two candidates stage a major catfight? If so, +1. Otherwise, +0.

5. Prominence? Did Bill Gates get elected? +2. Your local mayor? +1. You? +0.

6. Unexpected? Did your dog win? +1. Otherwise, +0.

7. Human interest? Did your cute two-year-old win? +1. Otherwise, +0.

Total: Up to 8, and the BBC will be calling from London. However, you're not going to score that high. (Can you elect both Bill Gates and your dog? Most people would say no.) Likely you'll score in the range of 2. This means your story may become news, but only on a slow news day, and will likely not place very prominently. It won't make the more severe cut of broadcast news at all.

This News Value-ator is based on average news values assumed by average gatekeepers. But lots of news organizations aren't average. They have assigned different weights to each of the news values above. We might call this their "view of reality." and we'll talk more about that in the next chapter.

More to Read

Z-Pattern, Basic Design Principles

Theodore E. Conover, Graphic Communications Today. 2d ed. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co., 1990, 153-177.

News Values

Melvin Mencher, Basic Media Writing. 5th ed., Dubuque, IA: Brown and Benchmark Publishers, 1996,118-126.

History of Early American Journalism

Wm. David Sloan, ed. The Media in America. A History. 8th ed. Northport, AL: Vision Press.2011. Chapter 3.

News Holes and Advertising

Leo Bogart, Press and Public. Who Reads What, When, Where, and Why in

American Newspapers. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1989, 45-73.

Sweeps

Nielsen: www.nielsenmedia.com; www.arbiron.com.

Press Agencies

Associated Press: www.ap.org.

Activities

Make a news story based on a day in class or at work. Which news values does your story emphasize? Which are missing?

Evaluate your group's news potential using the News Value-ator.